Like a long snapper on foot, even one at the Alabama power plant, Kneeland Hibbett doesn’t think about combing his hair through a lucrative approval deal.

What you earn, you need to use it.

The grandson of a Crimson Tide national champion, Hibbett pledged to donate some of his name, symbol and symbol to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, which works with former soccer players and others who have developed traumatic brain injuries as a result of repeated blows to the head.

Hibbett’s grandfather is possibly one of them. Catcher of Bear Bryant’s top-ranked team in 1965 that went on to play in the NFL, Dennis Homan still remembers how undefeated Alabama shed some other name through voting in 1966, but not, often, what he had for lunch.

“Kneeland was looking to do anything to honor her grandfather,” Missy Homan, Hibbett’s mother and Dennis Homan’s daughter, said in a recent interview. “To be on such a big stage, where the country is watching. . . What a scene to raise awareness about a disease affecting our family. “

The new regulations allowing school athletes to settle for cash in exchange for sponsorships are a boon to bigger stars like Alabama quarterback and current Heisman Trophy winner Bryce Young, who allegedly won more than a million dollars in deals with Dollar Shave Club, Fanatics and a local BMW dealership. .

But the ability to monetize one’s call, image, and likeness can also put cash in the wallet of star-studded players. Nebraska receiver Decoldest Crawford replaced his first one-time call in a deal with an Omaha air conditioning company; Missouri offensive lineman Drake Heismeyer saw an opportunity in his uniform number: 69.

“Practice for student-athletes is finding a way to excel,” said Blake Lawrence, executive director of Opendorse, which is helping school athletes navigate the NIL market.

“Some of them do it because they are in their position in the country. Others do it for being the most memorable on campus. And others do it by associating their call with a charity that other people care about,” he said. it’s a wonderful example of this. “

For Hibbett, it also means enjoying his connection with one of the most productive groups in the country, Crimson Tide, and with his grandfather, who is still well known enough in Alabama to be identified on the street every time he goes out.

Hibbett is the first school athlete to link his NIL earnings to a cause.

Michigan balloon carrier Blake Corum bought turkeys for families in need last Thanksgiving. Pittsburgh quarterback Kenny Pickett hosted an event for the Boys and Girls Club. Oklahoma quarterback Nick Evers donated the money from his first two-part NIL contract with Make-A-Wish.

But Hibbett’s cause is personal.

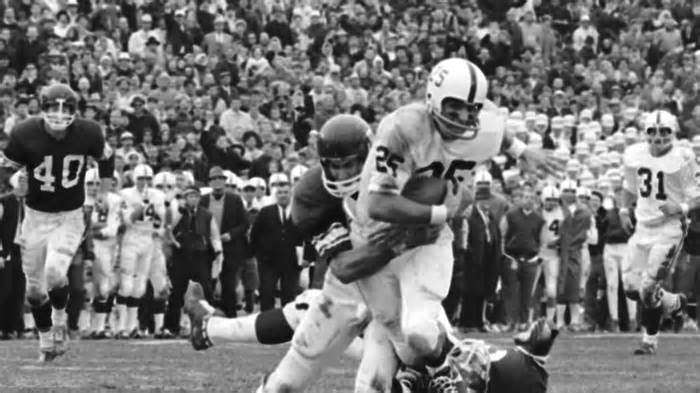

Dennis Homan, teammate of Ken Stabler and Ray Perkins, betting on Bryant on the Alabama team that won it all in 1965. (The 1966 team went 11-0 and finished third in the Associated Press standings. )

About 20 years ago, Homan’s circle of relatives began to realize that his memory was declining and suspected that he possibly suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease that affects athletes, the military and others who suffer repeated head injuries. be diagnosed posthumously.

Missy Homan said her father has so far escaped some of the more severe symptoms of CTE, which can cause violent mood swings and depression that can lead to suicide. He has stopped driving and his circle of relatives has learned not to ask him questions he would ask. you may not be able to respond.

“He is aware that he doesn’t do much, which is sad. But find out the humor in that, you know, saying, ‘I think I might have been hit too many times in my days,'” her daughter said. But its short-term reminiscence has still disappeared. “

Stabler, an NFL MVP who led the Oakland Raiders to the Super Bowl name in 1977, was diagnosed with TEc after his death in 2015. Perkins’ brain also showed symptoms of the disease.

Homan, now 76, promised his to Boston University’s UNITE Brain Bank.

“Once Kenny Stabler got his brain involved, he sought to do the same. And, you know, Coach Perkins and several other players in his time did the same thing,” Missy Homan said. “It’s like my mom is saying, ‘They’re teammates for life. ‘”

In a brief Zoom interview with Tuscaloosa, where he watched Hibbett play in a Crimson Tide preseason scrum last month, Dennis Homan spoke effusively about his grandson, not just for following him to Alabama, but for his position to do good.

“I’m telling you something, a lot more is happening than other people know,” Homan said. “But they’re doing anything about it. “

Hibbett declined to give the main points of the transactions he has made or could make, to say he would donate a “good chunk” of his source of income to CWF. He said the most he was introduced to was posting things on social media. ; his TikTok account, which is a combination of cute videos and him playing guitar and singing, has 262,000 fans and more than 14 million likes.

As an unknown snapper, Lawrence said, Hibbett’s profit outlook is likely in the thousands. “And if Tuscaloosa’s fan base supports it, it can turn into tens of thousands of dollars pretty quickly,” he said.

But it’s not just about money.

Chris Nowinski, founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation who played soccer at Harvard, said the opportunity to raise awareness about traumatic brain injuries in sports is even more important.

“If football players are mobilized to fight CTE now, we may be able to cure CTE during their lifetime,” he said. “But many of them are on the sidelines, ignoring the threat or praying to be one of the lucky ones who won. expand CET.

___

No more AP school football: https://apnews. com/hub/school-football and https://twitter. com/ap_top25. Sign up for the AP: https://bit. ly/3pqZVaF