To review this article, My Account, then View Saved Stories

To review this article, My Profile and then View Saved Stories

By Paul Grimstad

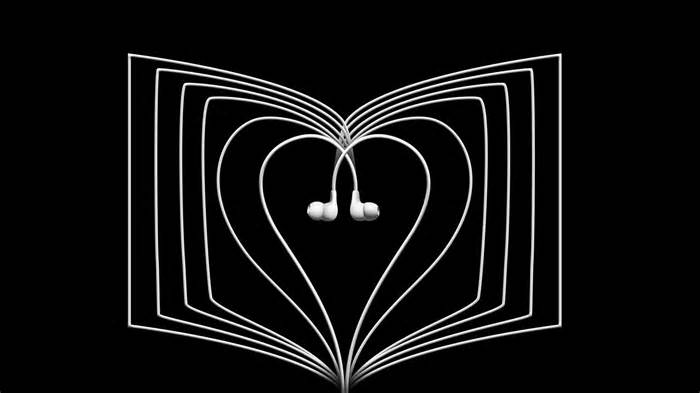

As a compulsive reader of physical books, I tend to think of an audiobook not as an auditory counterpart to print, but as a portable verbal environment that accompanies an errand or daily hustle. I don’t drive and haven’t had a valid driver’s license for twenty years, so I never have the chance to tackle, say, all of “Beowulf” or “Don Quixote” on a normal trip. But I discovered “The Waste Land” while standing in line at the post office, I heard Richard Feynman’s electromagnetism on exercise 7 toward Citi Field, I heard Marx anatomize the form of the commodity while surfing the trails of Van Cortlandt Park, I heard Marx anatomizes the form of the commodity while walking the trails of Van Cortlandt Park. Iris Murdoch’s swirling phrases in my headphones while I order an everything bagel (lightly toasted). Once at Key Food in Riverdale, I became so entranced by the mellifluous creaminess of Jeremy Irons reading “Lolita” that, in my fugue state, the names of the other types of Triscuit on the shelves were mystically added to the monologue via Humbert Humbert. : “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, fire roasted tomato, smoked gouda, touch of sea salt, avocado, cilantro and lime.

Although audioeebooks have their origins in recordings made for the blind as early as 1948 (Helen Keller called those ebooks “the most valuable tool for the blind since the evolution of Braille”), they now shape their own media ecosystem with production awards and interpretation. (Audies), engaged online forums for review and rating (AudioFile magazine), and editors’ “beginner’s guides” to cultivating a citation with audioeebooks. The audiobook’s rise to true aesthetic autonomy came with the arrival of the iPod and its MP3 disc format in 2001, and, as of 2023, more than a portion of the US population has listened to an audio ebook (in Sweden, sales are superior to those of hardcover ebooks). . And while it’s tempting to value audiobooks over physical ones, it’s really anything. Of course, you’re not free from casually rereading, resetting a paragraph, skimming the table of contents, flipping the e-book over to scan bland presentations, or all the other disjointed, non-linear things we do with e-books. And the rhythm is fixed, although not completely; You can adjust the speed in quarter increments, giving you a variety of options, from the lowest soporific setting, 0. 25x, to the high end caffeinated, 2x. And audioeebooks are not at all the same as a podcast. The latter are messy, warts and all kinds of talk, leaving out all the ‘ums’, ‘likes’, giggles and sobs, while an audiobook is a synthetic, edited and refined production.

The incredibly popular celebrity autobiographies read through the writer are an example of the audiobook as a production that can be fed as you would a movie or a playlist. Springsteen’s memoir, “Born to Run,” begins with the riff of the title song, and then Bruce comes in reading like one of the no-nonsense gas station guys in his songs. His occasional podcast partner, Barack Obama, reads his own e-book “A Promised Land” (a version of the name of a Springsteen song, by the way) in those pleasantly elongated Chicago diphthongs that we know so well and that give it an air of positive. He can develop a faith around David Lynch by reading his e-book “Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity. ” Lynch’s voice oscillates between Howdy Doody squareness and strange, disarming metaphysical injunctions, as when he advises the listener to avoid the “suffocating rubber clown suit of negativity,” urging us instead to “dive within. ” (Also, every bankruptcy begins with an ominous “Eraserhead”-like hiss. ) One of those genres I like is “I Am Keith Hernandez,” read by Keith Hernandez, a member of the wonderful Mets lineup that won the 1986 World Series. I listen to Keith on cable TV a couple of times a week during the baseball season, so in the offseason I comfort myself by listening to him tell stories about his problems with drunk umpires in the minor leagues, all the way up to becoming an eleven-time winner of the baseball glove, gold, and his appearances as himself on a few episodes of “Seinfeld” (not to mention his doctoral-level knowledge of the science of typing along the way).

Listening to authors from the more open literary spectrum read their own books can bring new dimensions to the voice we know on the page. Recently, after a long wait at the T. S. A. At LaGuardia, I heard the defeated David Foster Wallace read an excerpt from his nonfiction collection “Consider the Lobster. ” Wallace has an adenoid, slightly choppy reading style that brings out the humor in its pyrotechnic verbosity, and the title essay includes a truly inventive audiobook device: both once Wallace switches to one In his twisted, protracted footnotes page, a clear adjusts the equalization of the sound to delimit it from the main text. Nicholson Baker, who plays the fictional character Paul Chowder in his novel “The Anthologist,” sounds like a children’s television host on PCP, saying things like “the truth smells like Chinese food and sweat,” while Robert Caro’s memoir about procedural writing, “Working,” pairs perfectly with his sky-high New York accent, in which both one and both one and both one and both “time” is toyim, both one and both one and both one and both “stand” is stay, both one and both one and both one and both “fast” are fayists.

Then there are other people’s featured e-book readers (like Irons reading “Lolita”). In some cases, paintings beyond a narrator can influence the listening experience. The encouraged selection of James Earl Jones reading the King James Bible, glorious throughout, is also reminiscent of Lord Vader imperiously commanding to love his enemy. The icy kitchen of Joan Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” read by Diane Keaton, creates a disorienting (and not entirely unpleasant) collision between Yeats’ apocalyptic poem with which the e-book begins (and which provides Didion’s title) and the reminiscence of that message. – tennis, Ralph Lauren’s shabthrough-chic style consisting of an oversized “Annie Hall” vest, tie and trousers. Sean Penn reading Bob Dylan’s “Chronicles” made me believe in a mix of Jeff Spicoli and Harvey Milk giving birth to a kind of Dylan cosplay entity.

Professional voice actors tend to favor more animated performances, even adopting other timbres for other characters. In one of the audiobooks of Dashiell Hammett’s “The Maltese Falcon,” the male narrator switches each time to the trembling falsetto of femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy. speaks, while in Agatha Christie’s “The Mystery of the Blue Train,” Hugh Fraser’s elegant third British film. The user becomes something like a central captain of the casting industry fused with a cowboy when American millionaire Rufus Van Aldin appears. (Christie’s Americans are still millionaires. )

In some cases, an audiobook’s narrator is so flashy and unique that its functionality threatens to usurp it as the main attraction. My normal immersion in Henry James’s prose is at this point so intertwined with Flo Gibson’s voice that I can’t read “Daisy Miller,” “Another Turn of the Screw,” “The Ambassadors,” or “The Golden Bowl” without hearing his clear, musical, intelligent voice, which reminds me of a human owl. (Gibson, who died in 2011, had a career dating back to the golden age of radio and was named “Best Storyteller” through the Audio Publishers Association. )

There is also an effect where other books read by the same narrator can seem to group together into one bastard superbook. The audiobooks of Norman Mailer’s “Miami and the Siege of Chicago,” Steven Pinker’s “The Sense of Style,” and Nabokov’s epic “Ada” are read through Arthur Morey, and I began to listen to his circumspect, weary enunciation of the world. they coalesce into imaginary paintings in which the 1968 Republican conference is satirized between episodes of harassing the reader over sentence construction, all in Nabokov’s incredibly cold and backward prose. Many of my beloved science fiction audiobooks are read through Robertson Dean, whose voice sounds like a glob of pomegranate molasses falling off the edge of a spoon. It’s a clever compatibility with near-future technological dystopias, whether flat or resonant, that say things like “[she] lay looking for a faint anamorphic view of the repeating insectoid vessel” (c is taken from “Zero” via William Gibson. History). Dean is also reading “Arsenals of Folly: The Making of the Nuclear Arms Race” by Richard Rhodes, a leading historian of nuclear weapons, a sidebar that fits neatly with the ecological catastrophe paintings of much science fiction.

And then there are the guerrilla readers in the public domain, the tape recorders who take any Poe or Plato, any “Moby-Dick,” the diaries of Lewis and Clark, or the history of Egypt, in eccentric feats of staying in power. under hugely variable microphone quality and adding unheard-of lip smacks and omitted “P” and endearing attempts to correctly pronounce the original languages. There’s an illuminated audio from the Wild West, all loose (via LibriVox).

And what about the many untapped hybrid possibilities?How about prose paintings born from audio with sound design?Or give the listener a selection menu among other timbres or playback styles, or the ability to load a summarized background texture (white noise navigation, generator hum, soft rain, urban noise)?Or books with reading lists to combine with other sections at the reader’s discretion?(I don’t know, at this point, how licensing and legality of intellectual assets is intended to combine with all this, which would probably be beyond Byzantine. ) Such hybrid artifacts would possibly involve a new bureaucracy of understanding, or perhaps simply anything we don’t know about. I still have a name. In the meantime, I await the imminent arrival of audiobooks that I wish existed but didn’t exist: could we see Benedict Cumberbatch reading Douglas Hofstadter’s “Gödel, Escher, Bach,” Cate Blanchett reading Iris Murdoch’s “The Sovereignty of Good”?” or Dave Chappelle’s “Hamlet,” please? ♦

In the weeks leading up to John Wayne Gacy’s scheduled execution, he was far from reconciling with his fate.

What worked in HBO’s “Chernobyl” and what went extraordinarily wrong.

Why does the Bible end like this?

A new era of strength competitions are the limits of the human body.

How an unemployed blogger proved that Syria had used chemical weapons.

An essay through Toni Morrison: “The paintings you make, the user you are”.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker.

By registering, you agree to our User Agreement, Privacy Policy and Cookie Statement. This site is made through reCAPTCHA and Google’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Stephanie Burt

By the New Yorker

Sections

More

© 2023 Condé Nast. All rights reserved. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our User Agreement, Privacy Policy, Cookie Statement, and your California Privacy Rights. New Yorkers can earn a share of sales of products purchased through our site as part of our component partnerships with retailers. The fabrics of this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used unless you have the prior written permission of Condé Nast. Ad Choices