To review this article, select My Account, then View Saved Stories.

To review this article, My Profile, then View Recorded Stories.

By Richard Brody

It takes a cinematic and educational stranger to dive into the deep waters of academic discussion with brazen verve, as Robert Steven Williams does in the documentary “Gatsthrough in Connecticut: The Untold Story” (airing on Amazon). The film is rooted in the same theory that Barbara Probst Solomon (who is the main subject of the interview in the film; she died in 2019) featured in a notable 1996 play in The New Yorker: This First Model of F. Scott Fitzgerald for Jay. Gatsthrough’s West The Egg Estate and the cabin on its assets that Nick Carraway rents is not Great Neck, Long Island, but Westport, Connecticut. For Williams, as for Solomon, who was from Westport, the consultation was as private as it was historic. Williams, an executive in the music industry, moved to Westport in 1992 and has taken an interest in local history. He heard summaries of Fitzgerald’s connection to Westport and eventually, after Solomon’s article appeared, he partnered with local historian Richard (Deej) Webb to further his research. The stakes in educational disputes are said to be low, but Williams enthusiastically shows, over the course of the film, that geographic reference is more than a footnote: it is the key to a fair appreciation of literary art. through Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

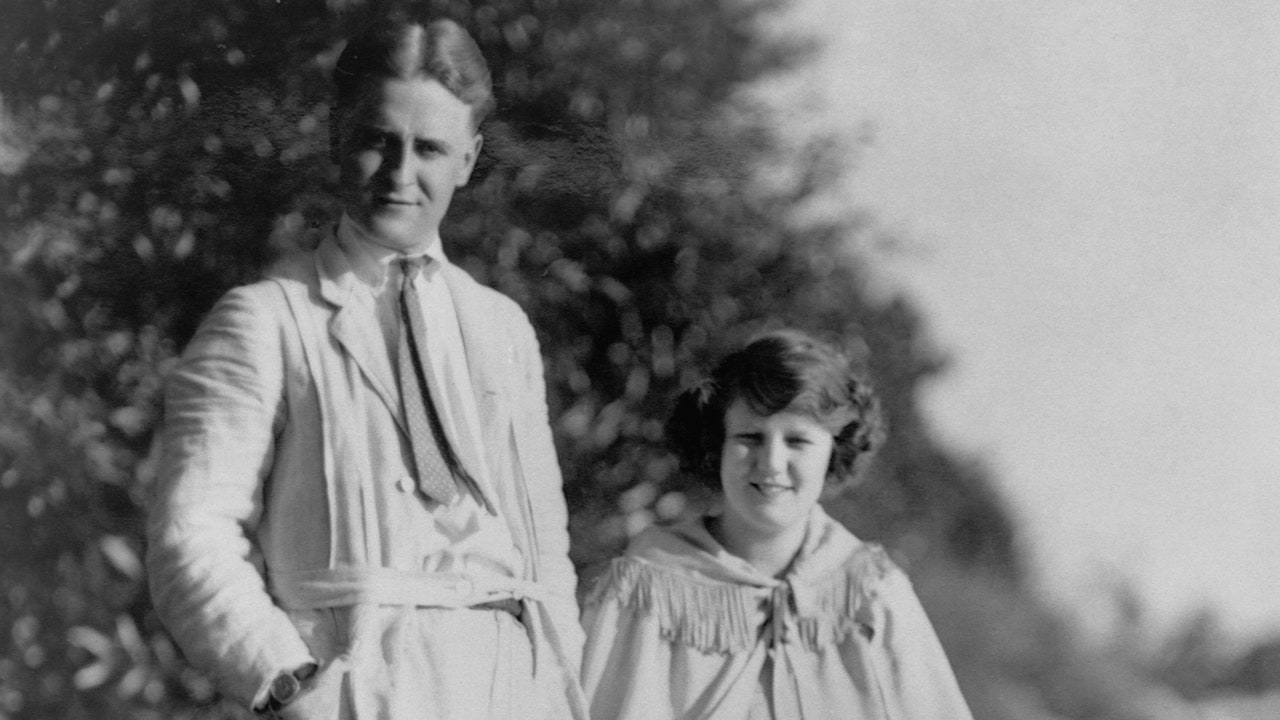

The case presented through Williams and Solomon begins with the geography of the Westport assets where the newlyweds Fitzgeralds lived, for five months, during the summer of 1920, some time after the publication and acclaim of the first novel by Scott. Paradise. “The young couple (Scott was twenty-three; Zelda, nineteen) lived in a cabin on the edge of a wealthy man’s estate, similar to the one Nick lived in on West Egg; the shore at the edge of these assets in the water The edge offered a view across the bay to a magnificent dock (the one that belonged to the luxurious space where Solomon grew up), similar to the one celebrated in “Gatsthrough.” Also, the rich and secret industry of the Baron, Frederick E. Lewis , who the Fitzgeralds rented from and whose mansion was on the beach component of the estate, hosted nights of colossal frenzy and frenzy, with circus animals and Broadway stars and Harry Houdini. And John Philip Sousa hired to play. (The Pool de Lewis also had a tower similar to the one Gatsthrough’s visitors threw themselves into.) The Fitzgeralds attended at least one of its components, and behaved in a manner scandalous enough to be excluded from any event of their future, even which allowed them to access their personal beach.

The lively and diligent studies leading up to the identity of the novel’s main site is just one of the many virtues of “Gatsthrough in Connecticut,” all of which stem from Williams’ role as a movie newcomer. When he started working on the assignment in 2013, having never made a movie before, he was making plans to make a short film for local use, but his success spread along the way. Like an enthusiast who came to scholarship here by chance, he approached the main points of Fitzgerald’s life and worked with a whole new eye and an unshakable sense of wonder. It unfolds in extremely joyful and moving detail the story of Fitzgerald’s wild summer of 1920, emphasizing the rush for riches and fame that went to their heads when “This Side of Paradise” became a hit. Widely acclaimed reviewer and an instant bestseller. Interview subjects and archival quotes (including one from Dorothy Parker) detail her glamor, fame, and charm; Williams calls them “America’s first rock stars.” In particular, the concepts of Solomon point to the same year 1920 as a critical moment of transition from culture to modernity, and the very fame of the Fitzgeralds, their youth, their unhindered freedom, as well as their artistic prestige, either as an emblem and an impulse. force this change.

The film cites Zelda’s 1932 novel “Save Me the Waltz,” which includes the main points of that wild summer of a decade of abductions, and also devotes careful attention to Scott’s novel of the moment, “The Beautiful and Damned. From 1922, which he wrote in the warmth of the stunning romantic extinction that is itself the tale of the novel. Williams associates the action of “The Beautiful and Damned” with a map of the city and photographs from the period, and quotes a letter in which Scott wishes the novel to be more “mature” because it has the unique exceptional characteristic of “being” all true. This is also a component of the exceptional characteristics of “Gatsby in Connecticut”: his rehab of “The Beautiful and Damned “, which for me is Fitzgerald’s most moving, gripping and heartbreaking novel. It is not a jewel carved like” Gatsby “, it is not an epic tragedy like” Tender is the night “, however it is scene making wedding more Fitzgerald’s convincing and less inhibited portrait, a heartless and haunted portrait of a couple, as he himself wrote, “Castaway on the Banks of Dissipation”; as Fitzgerald himself asserts, they did not do that to themselves: they made themselves. (In saying this, Scott would possibly have been simple with himself: Williams also shows Scott’s confidence and propriety in Zelda’s inspiration and art, and outlines the threads of anguish that resulted from his use of his diaries and letters in the novel. and the blatant control he exercised over his life and his art).

Williams evokes the Fitzgeralds and their times with voice-over narration (played by actor Keir Dullea) combined with movie clips and still images, archival posts and art paintings, maps and existing footage, all connected through music recordings of roughly (sometimes very roughly) the same period. . It’s a familiar, even conventional format, but Williams embarks on it with as much enthusiasm as if he had discovered it himself, energetically reliving the Fitzgeralds and their times. His sense of wonder and joy at the discovery also continues with his academic studies, such as when he makes notable detective paintings to locate the diaries of Fitzgerald’s school friend Alexander McKaig, who was in a position to practice the pair in dismay. detailed. riot behavior. The investigation is incorporated into the film with spontaneous cinematic inventiveness and lighthearted reflexivity, as Williams films himself and Webb at the academy corporation, in study rooms, and also at the former Fitzgerald House in Westport, with Charles Scribner III (the grandson of the editor F. Scott Fitzgerald) and Sam Waterston, who played Nick Carraway in the 1974 film “The Great Gatsthrough.” They also film a moving interview with Bobbie Lanahan, Fitzgerald’s granddaughter and full-time biographer, who stores the effects of her own studies and conducts revealing local studies among Westport residents.

Williams’ educational controversy was sparked through the publication of Solomon’s article.After its publication, Matthew Bruccoli, Fitzgerald’s long-time lead researcher (who died in 2008), casually rejected his findings.In “Gatsthrough in Connecticut,” several participants criticized him for his unique technique to Fitzgerald’s life story and even his texts.In addition to the express concepts it details, the film considers the very perception of literary erudition and what it is for.Although “Gatsthrough in Connecticut” illuminates the mysterious corners and nooks and crannies of “The Great Gatsthrough, “it does much more: bring studies to life and make the study procedure private and exciting, it shows that the risks of such conflicts are strangely and sustainably high.In the procedure, the film exposes and corrects specific procedures through which weapons and hierarchies are established and perpetuated.In its warm and individualistic vigour, “Gatsthrough in Connecticut” is a valuable painting of literary denunciation in cinematic form.

It will be used in accordance with our policy.

By Ian Frazier

F.Scott Fitzgerald is one of the limitations of your experience.

By John C. Mosher

New York film critic Richard Brody, in verbal exchange with R.L.Lipstein, discusses 4 fantasy clips.

The director’s new film, which airs on YouTube, explores the clash between the hallmarks of a sedentary (active, business, active) and the primitive force of romantic passion.

By Richard Brody

sections

In addition

© 2020 Condé Nast.All rights reserved. Use of this site is an acceptance of our user agreement (updated 1/1/20) and our privacy policy and cookie (updated 1/1/20) and your privacy rights in California.The New Yorker can earn a portion of the sales of products purchased on our site as a component of our component associations associated with retailers.The content on this site may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used, unless you have the prior written permission of Condé Nast.Ad selection